Doctor Who: The Eighth Doctor Adventures

#16

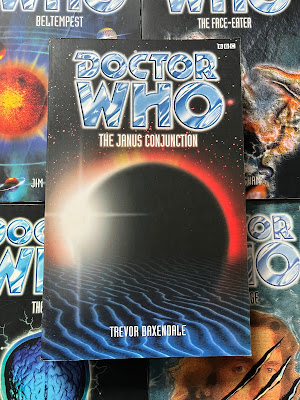

The Janus Conjunction

By Trevor Baxendale

There’s nothing like a new author to shake things up a bit. Here comes Trevor Baxendale with a story about human factions fighting over an abandoned alien artefact that doubles as a doomsday weapon and… actually, are we sure this is a new guy?

Certain tropes are bound to spring up in a long running series — especially one based on a long running series! — and the BBC Books run seems to have a few of its own by now. We’ve already had severely narky groups fighting over a dangerous alien thing in Longest Day and Vanderdeken’s Children. Alien ruins appeared and were utilised in both of those, as well as Alien Bodies, Kursaal, Option Lock, Seeing I, Legacy Of The Daleks and Last Man Running. Probably others too. It’s starting to look like a default setting: want to do SF? Have humans abusing, or wanting to abuse old alien tat for their own evil aims. Just add TARDIS.

This is pretty reductive, of course. It would be silly to put down books like Alien Bodies or Seeing I just for including familiar ideas. As I seem to say quite a lot, it’s what you do with your ideas that counts. And The Janus Conjunction… well… it doesn’t exactly reinvent the wheel there either. But I think it does This Sort Of Thing better than most recent attempts. And I think there’s genuine merit in that.

Right away we’re plunged into a warzone on the eerie world we can see on the cover: permanently eclipsed, with strange blue luminescent sand for lighting, this is Janus Prime. Soldiers in sealed suits are attacking a few visitors from Menda. What their actual beef is, we don’t yet know, but it’s an exciting start that introduces enormous cybernetic “spidroids” and ends with a very well timed wheezing and groaning. The Doctor and Sam instantly fall in with the Mendans, but are then separated by the Link — a mysterious gateway to the sister planet on the other side of their dying star. The Doctor is now on Menda. Sam is now in trouble.

The longer Sam is on Janus Prime, the greater the risk of (spectacularly!) fatal radiation poisoning. But the occupying military figures are not sympathetic types. The Doctor, meanwhile, has to talk the more peaceful (but just as stubborn) Mendans into letting him rescue his friend — as well as stopping whatever it is the maniacal Zemler is up to over on the dark planet, which has something to do with the Link.

It’s worth mentioning here that they’re all human. In a bit of continuity that for once actually puts old stories to work in a way that inspires new ones, we learn that following the Dalek occupation humans made some scrappy efforts to visit the stars. One of those was to set up a colony on the fairly remote Menda. They were escorted by mercenaries led by Zemler, a disgraced military figure who wanted to stay busy. On arrival/crash landing, when it became apparent the mercs couldn’t go home, the mood turned sour. Following the discovery of a strange portal to the neighbouring Janus Prime, Zemler and co found a new lease of life — somewhere to go, a planet to conquer — however this turned out to be an irradiated dump and returning to Menda after too much exposure meant instant death. Worse, the Link couldn’t be used to get them back to Earth. The end result was a pack of mercenaries who hate Menda, and a mysterious Link sitting between them in Chekhov’s Gun fashion.

There’s not a lot of varied motivation here. The Mendans like their planet and Zemler’s troops are mad about stuff. I think, putting on a somewhat charitable hat, there’s a unifying idea here about people trying to make their way and struggling to deal with the consequences of that: the Mendans want a colony, Zemler wants to maintain a kind of career after disastrous crossfire ended his time in the military. With the added continuity (which I like in this case!) it does sort of loosely become a story about What Mankind Did Next, and the different impulses that might drive that — wanting the best for everyone vs wanting the best for yourself. I don’t know if I’d go so far as to call it the book’s theme — to the extent that it is, it must be a fairly late addition, Zemler’s gang having been aliens in early drafts — but it gives you something extra to latch onto if you want.

Because… yeah. The characters aren’t terribly interesting otherwise. Don’t get me wrong, we’ve had worse, and I think they all function pretty well within their limits, but there are limits. Julya wants her colony to thrive and she sort of likes Lunder. Lunder is an ex-mercenary who grew a conscience, so he has history with Zemler/a tension with the mostly peaceful colonists, and he sort of likes Julya too. His loyalties don’t wobble as much as you might expect. (A moment where he openly talks a character into self-sacrifice rather than do it himself makes rational sense, but it’s still pretty mean and goes completely unexamined by the Doctor.) Of the rest of the colonists, few register at all, and Menda is pleasant but dull as a rock — basically your average somewhat old-timey Star Trek outpost. An odd thing to get killed over.

The mercenaries are pretty much going along with their mad boss because they’re all dying anyway and it’s something to do. (When one of them switches sides it happens between scenes, so we skip the actual interesting bit.) Zemler is an absolute Emperor Zurg-level bad guy, sitting in an evil lair stroking a pet. He seems openly resistant to any rational reason for what he’s doing, starting off generally annoyed and sinking into megalomania from there. When the story finally starts playing around with the doomsday device, however, with all the technobabble that creates, it’s sort of nice that the stakes are so clear. One guy hates everyone so much that he’ll destroy everything. Okay, that’s a very quantifiable problem if nothing else.

Again with the charitable hat: I don’t think it’s that hard to empathise with these different groups. The Mendans have a nice home, of course it makes sense to protect it. The mercenaries are dying, and dying horribly, so it makes an awful kind of sense that they’d want to lash out, and otherwise have no better ideas than just “whatever the boss says”. Baxendale underscores the point by putting a lot of effort into the horrors of radiation, bodies rotting until they die at which point they instantly liquify. You’re always horribly aware of what’s happening to them, or what’s going to.

I think he just about pulls back from revelling in it, with the cost of it weighing on Sam for a lot of the book. She really puts her principles to the test here, hanging out on Janus Prime (at certain points, voluntarily) and putting herself at risk to help others. She suffers greatly for all of that, getting visibly sicker until she actually dies — a spoileriffic thing to blurt out, I know, but it’s also a thing that is resolved within 5 pages in a way that Sam won’t notice and the Doctor didn’t either, which I think makes it okay to mention here and perhaps makes it a contender for the all time Damp Squib Awards. (I wonder if that brush with/actual encounter with death will somehow come into play at a later date. I suspect that, like her possession and unwitting crimes in Kursaal, it won’t.)

There’s some pretty good interrogation of Sam’s stance on guns (Genocide still casting a shadow it seems), with the awkward bonus that her attempt to create a distraction ends up taking alien lives. She never actively finds out about this, although I very much enjoyed the subtle suggestion that the Doctor tells her via a psychic bond. (“The explosions had stopped the moment the Doctor found out it was Sam using the ripgun.”) Perhaps it’s fair to spread the bad feelings about; the violence here, after all, emboldens the Doctor’s characterisation. He gets to display not only a literal, mental link with the spider creatures/Janusians, but he empathises strongly when they are killed, more so than anyone else around — and he rages when it’s done deliberately by Lunder.

The Doctor here is as dead-on as he gets, a whirlwind of charm that can turn instantly to serious consideration instead. He confronts Zemler fearlessly (albeit perhaps foolishly) and his distress at realising Sam has unwittingly taken lives is as palpable as when he realises just how ill she has become. He displays a pleasing amount of cheekiness as well, at one point using the TARDIS’s temporal orbit to sort out a problem without advancing the overall ticking clock (he should do that every week!) and at the end steering himself and Sam away from a party because “I’ve seen the future and we don’t go.”

The best thing about The Janus Conjunction is the pace. It doesn’t let up, leading to a highly readable story that only looks as if it’s dragging its feet near the very end. The constant and very visible threat of radiation, plus the equally constant, equally visible moon and sands of Janus Prime (and the danger they represent) propels the thing along even though it is, in all honesty, a meat and potatoes Doctor Who story, and a familiar one at that. The writing for the regulars is excellent; the writing for everyone else is good enough. I doubt it’s anyone’s favourite, and I’m very ready to move on from alien wreckages and doomsday machines, but it’s a very solid bit of work.

6/10