#24

The Final Sanctions

By Steve Lyons

War. Huh. You know what, I think I’ll give it a miss.

The last time we saw the Selachians was their introduction in The Murder Game, a light-hearted low stakes romp. They were an incongruous menace, aquatic beings in bio-mechanical suits with sharks painted on the outside, out to destroy all land-dwellers. They posed an obvious threat but were just the teensiest bit silly.

Steve Lyons strikes an entirely different note in The Final Sanction, and he makes that clear right away, landing the Second Doctor, Jamie and Zoe in a warzone. (Hey, there’s an idea.) The first chapter chops up events in a way that Lyons has enjoyed doing since The Witch Hunters: Zoe is having such a miserable time that she’s already remembering their arrival and considering its importance in coming events. This has the effect of starting the story already on the go, which also helps to raise the urgency of what’s happening. The sight of many dead aliens also drives that point home.

The planet Kalaya is one of the last holdouts in the Selachian war with mankind; if they can be driven back from here, all that’s left is their homeworld, Ockora. The trio quickly encounters the two opposing forces. They are, of course, separated, with Zoe becoming a Selachian prisoner and Jamie joining the Earth forces to fight. The Doctor has his own problems: he knows that some time soon the humans will use a catastrophic weapon to destroy Ockora, killing the Selachians and a large number of innocent hostages. Worse, since this is established history he cannot stop it — he must ensure it happens. And now Zoe’s in the firing line.

Tragic inevitability is another holdover from The Witch Hunters, but this doesn’t feel like a repeat as Lyons gets to paint on a much broader canvass this time. The destruction of an entire world is not some subtle chain of events like the Salem witch trials, and this time the problem isn’t remotely the fault of the TARDIS crew. The scale of the problem is so enormous that the tragedy itself is surely much greater, although by the same token it’s so overwhelming that it’s almost impersonal. (Not to mention, entirely fictional.) Frankly, it’s not as if there are many Selachian protagonists around to make us really identify with what’s happening beyond the obvious fact that it is genocide. Unlike The Witch Hunters, and to its detriment, there is never really a plausible path to not carrying out the tragic event.

The point is perhaps further muddied by making this a tragedy about hostages caught in the crossfire — of which Zoe is very keen not to be one, with the Doctor and Jamie in vigorous agreement, thus keeping them all on some level thinking about something other than the impending Selachian tragedy. The most direct reckoning with this horrendous war crime comes in the form of Dr Mulholland, the expert behind the G-bomb who is doing her best to distance herself from its inevitable use. Over the course of the book her defences break down and she faces her part in this. The various military characters we get to know — all troubled men with varying levels of insecurity — never quite reckon with their choices.

For good measure, at least one Selachian does reckon with the scale of what has been lost, thinking of his beautiful home and family and then momentarily losing respect for his superior, saying “you should have surrendered.” More Selachian characters seems an obvious note here: the one I’ve just mentioned gets comparatively the most to do, being instrumental in Jamie’s eventual realisation that they are not merely monsters. His resolute hatred of humanity remains, however, and this is much of a piece with how they all behave, making them (perhaps cleverly but not helpfully) hard to like. The only Selachians not rampaging about are the non-combatants, of whom we only meet a few; they tend to die tragically without sharing their points of view, their deaths being yet more fuel for their already furious brethren. I don’t get the impression that the non-military way of life has disappeared on Ockora (at least not while Ockora exists) but it would have been nice to hear more about it.

The tragedy of the Selachians is ultimately posited as one of abuse — the Kalayans having cruelly mistreated them and stirred their hatred of all land dwellers — and then one of stubbornness. But firstly, the Kalayans hardly feature in this, and the one that we do meet (Kukhadil) doesn’t have occasion to feel bad about his people’s part in these events. In the context of the fighting here, the Selachians feel much the same about everybody who isn’t a Selachian, so it seems a bit redundant that their “true” enemies are involved. Secondly, it’s not as if anyone puts forward an idea of what a Selachian surrender would actually look like in practical terms. The local Earth military leader, Redfern, gives no indication that he’s not just in it for the kill count.

I suppose what I’m saying is, this is not the most nuanced take on the horrors of war. The ingredients are all there, with intractable military leaders on both sides and innocents in the middle, but there’s a certain A-to-B feeling about the execution, with all the Selachians following much the same pattern and, to be honest, most of the humans doing that too. Lyons is Doing A Thing there, I know, but he doesn’t find many opportunities within that to say a great deal that’s new, although there is a bright spot when the death of a soldier takes up an entire chapter; context leads us to believe that he is human, and then the rather sheepish reader is put right.

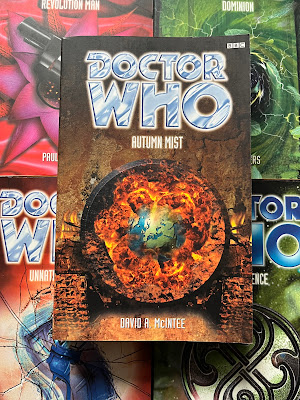

Perhaps recent books haven’t helped. Autumn Mist was a horrors-of-war story and Storm Harvest concerned multiple other bio-mechanical water-dwellers, some violent; those were the two books directly before this. I will say though that The Final Sanction makes the Selachians more interesting, achieving (in its modest warzone gravitas) a clearly separate identity from the Chelonians, who previously seemed a little too close for comfort. It’s a shame that, chronologically at least, we are unlikely to delve deeper into them as characters.

The book does a good job with its regulars. Steve Lyons is one of those very observant writers who can easily capture the characters’ voices, and despite the dark story there are some charming moments for the Doctor, all quintessentially Troughton-esque: “[The Doctor] dropped the brick and stood up, lacing his fingers together and giving his companions a familiar contrite look: apologising in advance for the fact that he was about to get his own way.” / “The Doctor’s expression suggested that all the misfortunes of the universe were a personal disappointment to him.” There is a darkness to him as well, which of course also fits, as he commits to the unhappy resolution long before it happens, and in the epilogue puts Zoe on the spot to consider whether she would have done things differently. (This is of course intended as helpful.)

Zoe and Jamie are very well defined here, sometimes in deliberate opposition: “Zoe could never be satisfied until she knew exactly how and why things worked.” / “The Doctor, [Jamie] supposed, must have worked some kind of magic. For Jamie, that was explanation enough.” Jamie’s enthusiasm for fighting is perhaps a slight stretch — ostensibly it’s out of the urge to rescue Zoe, but there’s a whiff of just wanting to get into the military thick of things again, with Jamie a little too easily thinking of the Selachians like redcoats and not as people. It serves a pretty clear purpose though of using a somewhat simple man (sorry, Jamie) to demonstrate the easy grip of fanaticism, and to Lyons’ credit the eventual contrite team-up with a Selachian isn’t the end of this journey, his new comrade being ultimately too keen on killing humans for Jamie to tolerate. Along the way he defaults to trying to emulate the Doctor, or at least what would be his choices, which seems a good way to cap it off.

Zoe’s story is, for her anyway, a less satisfying one. She’s escaping only to be recaptured for some of this — one of our oldest chestnuts — but built into that is a gradual attempt to apply her intelligence and lead others, with invariably poor results even despite her (so she reckons) higher intelligence than the Doctor. Being more cerebral than Jamie, she’s considering the wider questions, but also ultimately defaulting to the kind of mentality that drives the Jamies of this situation: just wanting orders from someone who knows what to do. A level playing ground, perhaps, to show that anyone can go along with war. So there are layers to all this; see also, where despite his objections the Doctor is able to steer inevitable events in small ways that lend people a bit more dignity — but rarely, alas, happiness.

I think The Final Sanction is an entirely decent war-is-heck story. I wouldn’t exactly describe it as fun, but as an action adventure it’s well crafted, Lyons sticking with groups of characters for long stretches and building momentum with cliffhangers aplenty. There are simply a lot of unexplored paths that could have made it stronger. A more diverse set of characters to invest in would have been nice. (Redfern, Michaels and Paterson could be more distinct.) More and varied Selachians and definitely more of their culture would have added meaning and pathos. (“Paul Leonard” it up a bit.) And more about the hostage crisis would, ironically, have helped, as this bit ultimately just disappears in all the noise. Nevertheless, these kinds of stories are worth telling. I didn’t love it, but it’s a creditable and confident effort.

7/10